Not Working for The Man

If you live in Europe, you get used to periodic labor strikes frequently affecting some aspect of daily life.

When we moved to Berlin in the summer of 2022, strikes by ground crews and baggage handlers at airports all over the continent nearly derailed our meticulously orchestrated adventure before it even began. I wrote about that here.

And I have written more about strikes and workers' rights in Berlin here and here.

But I'm not complaining.

We support organized labor. My husband is a member of the Ver.di union. And one of the main reasons we decided to move our family to Germany and the European Union was so our kids would start their working lives with more rights and protections than we had in the United States.

So, while it may seem – to American eyes – a bit crazy to walk out over a 37-hour versus a 35-hour work week, as the German train drivers' union did. The largest company employing those drivers paid their top management millions in performance bonuses that year, despite the record number of train delays and cancellations. If your management deserves performance bonuses, then so do the workers who actually perform.

More than half of all jobs in Germany are covered by collective bargaining agreements, despite only about 16 percent of workers directly belonging to a union. This is because agreements are usually worked out at the industry and regional level by unions and employer associations. The agreements set wages and working conditions across a large number of jobs and companies.

Companies that are not members of an employers' association are still often bound by the collective agreements for their sector. While they are not legally obligated to do so, many adopt the agreements as a standard.

If a company is covered by a collective agreement, non-union employees in that company typically receive the same benefits and terms as union members. Companies will often apply the contract to all workers to ensure equal treatment and avoid legal issues. And if the German Ministry of Labor declares an agreement to be "generally binding," then all employers in that sector must abide by its terms.

The right to strike

Of course, the ultimate leverage that unions have to get what they want is a strike - a coordinated refusal to work.

When negotiations between unions and employers break down, Article IX of the German constitution, the Grundgesetz ("Basic Law"), protects the rights of the unions to call for a strike. And article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights protects collective action as a part of the fundamental freedom of association.

However, German law also regulates who and under what conditions may go on strike.

For example, a strike can only be called by a union and employees can only participate if their job is covered by a collective bargaining agreement and their individual work contract directly refers to that agreement.

During the time of the strike, workers' contracts are considered suspended and they are not paid by the company, but they do receive daily strike pay out of union funds.

Certain categories of employees – those in the public sector and those employed by a church or church-owned companies, for example – are prohibited from striking.

Unlike in Italy and France, political strikes - strikes called exclusively to protest a government policy unrelated to a collective bargaining agreement - are considered illegal and workers risk dismissal from employment if they participate.

The west German general strike on November 12, 1948, which has been credited as the spark leading to the development of the country's novel social market economy, would likely be considered illegal today.

The difference between Europe and the U.S.

In contrast to the strong foothold trade unions have in European countries, organized labor in the United States experienced a precipitous decline in the later half of the 20th century.

In the early years of the Industrial Revolution, labor organizing and trade unions became very powerful and popular in the United States as they did in Europe during the same time.

Over time, though, anti-union legislation in the U.S. coupled with the willingness of state and federal leaders to deploy police and the military in support of corporate interests led to declining union particpation and a lack of support in the general public for organized labor.

"On Monday, July 16th, firemen and brakemen in Baltimore walked off on the job and began to halt freight trains. Word of the spontaneous strike spread along the B&O line, to Martinsburg, then Cumberland, MD, Keyser, WV, and all the way to Wheeling, WV. ...Almost immediately B&O officials demanded President Hayes to send out the military to crush the strike." (Linked article from the website of the Appalachian Forest National Heritage Area, accessed Nov. 22, 2025.)

"On the morning of April 20, National Guardsmen aligned with the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company attacked the Ludlow Tent Colony to try and break the UMWA strike, killing 21 people (including 11 children) in what became known as the “Ludlow Massacre.” (Linked article published by the National Park Service, accessed Nov. 22, 2025.)

Ironically, a key provision of the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (a.k.a. the Wagner Act), which guarantees Americans the right to orgnaize and participate in unions, requires that work contracts be negotiated between individual companies and unions, prohibiting agreements by region or sector as is the case in much of Europe.

The passage of the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947 (better known as the Taft-Hartley Act) reversed many pro-union elements of the Wagner Act and further outlawed several features of labor organizing and collective action, including solidarity strikes or general strikes (multiple unions striking together to achieve a set of goals), and wildcat strikes (strikes without union authorization). It also allowed states to pass right-to-work laws, laws that prohibit mandatory union participation and/or extending the benefits of a negotiated contract to non-union members.

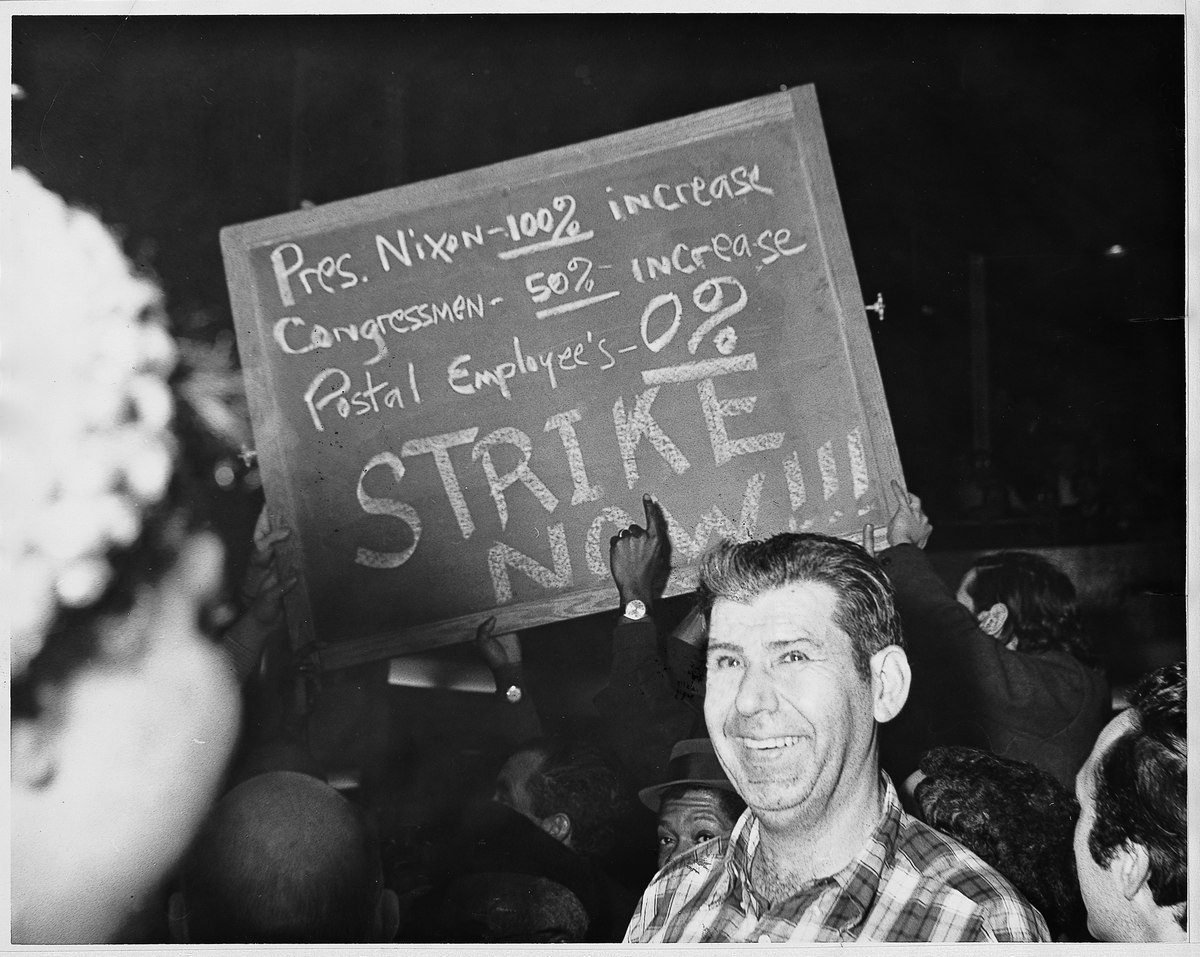

An eight-day 'wildcat' strike of more than 210,000 federal postal employees was opposed by union leaders. The end of the strike saw the dissolution of the U.S. Post Office Department to be replaced by the United States Postal Service. No postal worker lost their job over the strike, and the workers gained the right to engage in collective bargaining, though not the right to strike. (Link is to the Wikipedia entry about the strike, accessed on Nov. 22, 2025.)

But possibly the heaviest blow to organized labor in the United States happened in 1981, when then-President Ronald Reagan fired 11,000 striking air traffic controllers and banned them from any future federal employment.

The failure of the PATCO strike reshaped the American labor movement. Unionization within the U.S. steadily declined, from 20.9% in 1981 to 10% in 2024. The strike encouraged employers, with the backing of the federal government, to wield the threat of permanent replacement as a strikebreaking weapon. Consequently, labor unions grew more hesitant about going out on strike, and employers grew bolder.

Collective action works

The benefits to workers of organized labor are most clear when you look at the overall numbers - wages and jobs.

To use Germany as an example:

A 2022 paper published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives comparing industrial relations in Germany and the United States found that the greater bargaining power enjoyed by German workers was associated with lower income inequality, a larger manufacturing share of overall GDP, and less employment loss to technology.

Annual workhours are low, the low-wage sector is 25% smaller than in the US, and labor’s share of national income is higher. The German manufacturing sector still makes up almost a quarter of GDP (compared to 12% in the U.S.). Germany has one of the highest robot penetration rates in the world (IFR, 2017); yet in sharp contrast to the U.S. (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2020), robotization has not led to net employment declines in Germany, with local union strength associated with smaller reductions in manufacturing employment (Dauth et al., 2021). Relative to other OECD countries—many of which, like France or Italy, have maintained even higher collective bargaining coverage through more rigid bargaining systems—the German labor market features low unemployment and high labor force participation.

The national hourly minimum wage in Germany is currently €12.82 ($14.77) and set to increase in 2026 to €13.90 and again in 2027 to €14.80. In the United States, the federal hourly minimum wage is $7.25 (€6.30).

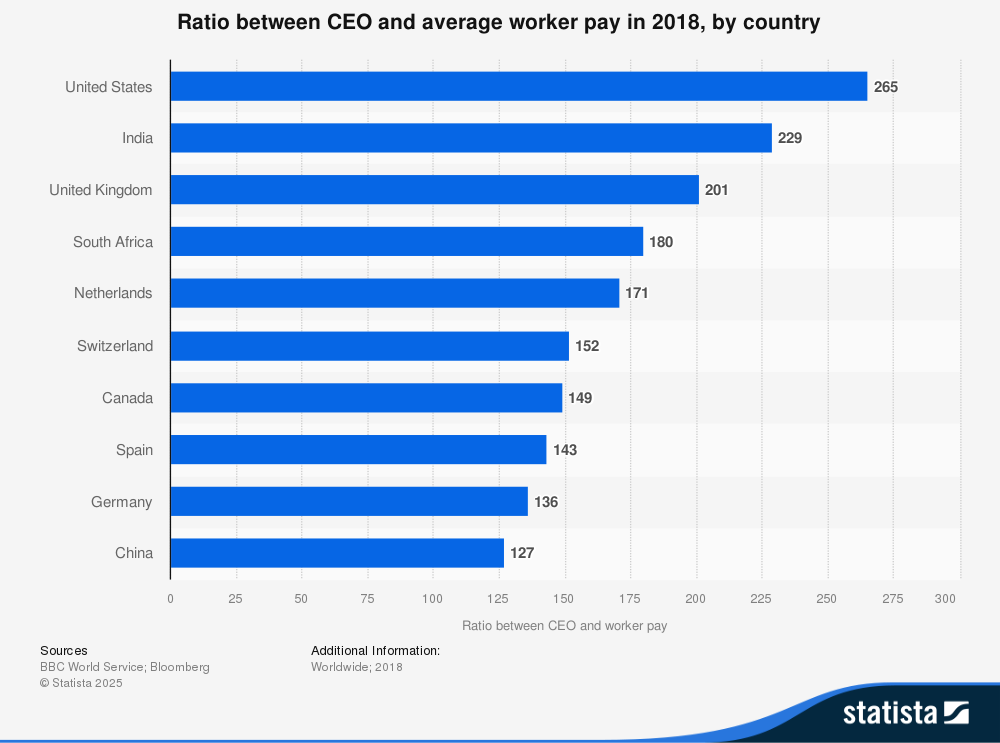

The compensation gap between workers and company executives is also narrower in Germany, with German CEOs making 136 times what their average worker is paid. In the United States, CEO compensation averages 265 times the average employee.

2025: Labor strikes back?

But, there are signs that the anti-worker tide is turning.

Even Germany is feeling the pressure as general strikes kick off in Italy, Greece, and Belgium against government austerity policies and foreign aid.

Numerous groups in Germany have called for general work disruptions as a response to anti-immigrant statements made by German Chancellor Friedrich Merz and the perceived lack of action on the rise of racism and far-right extremeism in the country.

Others are calling for an end to the ban on strikes by government employees and solidarity strikes by multiple unions.

In the United States, Shawn Fain, president of the United Auto Workers union, has called for labor organizers to stage a general strike on May 1, 2028.

Why almost three years from now?

That is the day that the work contracts for UAW employees at the "big three" U.S. auto makers expire. Fain has called on the leaders of other unions to adust their contract expirations to this date. This would allow numerous unions across multiple industries to strike at the same time, putting pressure on companies to make concessions.

And, the time frame also gives the vast majority of workers in the United States who are non-unionized time to organize.

After all, strikes won't work if not enough workers honor them. Companies and government leaders can just fire the strikers and hire more complacent replacements.

As Fain wrote in the left-wing weekly In These Times in 2024: "If we’re to build “enough collective power to win universal healthcare and the right to retire with dignity, then we need to spend the next four years getting prepared.”

And as Times' Associate Editor James Patterson explains, "The plan could include pressure not just on employers — but on the state itself. Coordinated issue campaigns and disruptive mass strikes across the country could give workers enough leverage to make bold demands, influence elections and fight Project 2025. And if unions band together, the working class could help move the needle on Medicare for All, debt forgiveness, a shorter workweek and other key demands."

When workers band together to demand fair treatment from their employers and their government, they are a powerful force. In the United States, collective action by unions and other workers' rights organizations are responsible for the eight-hour workday, 40-hour work week, and federal legislation mandating safe working environments.

At a time when corporate and governmental leaders are openly disregarding and seeking to roll back these hard-won protections, it may be up to workers to swing the pendulum back.

Read more about the 2025 general strikes across Europe

Read more about unions and the right to strike

Member discussion