How American Healthcare Got Here, part 1

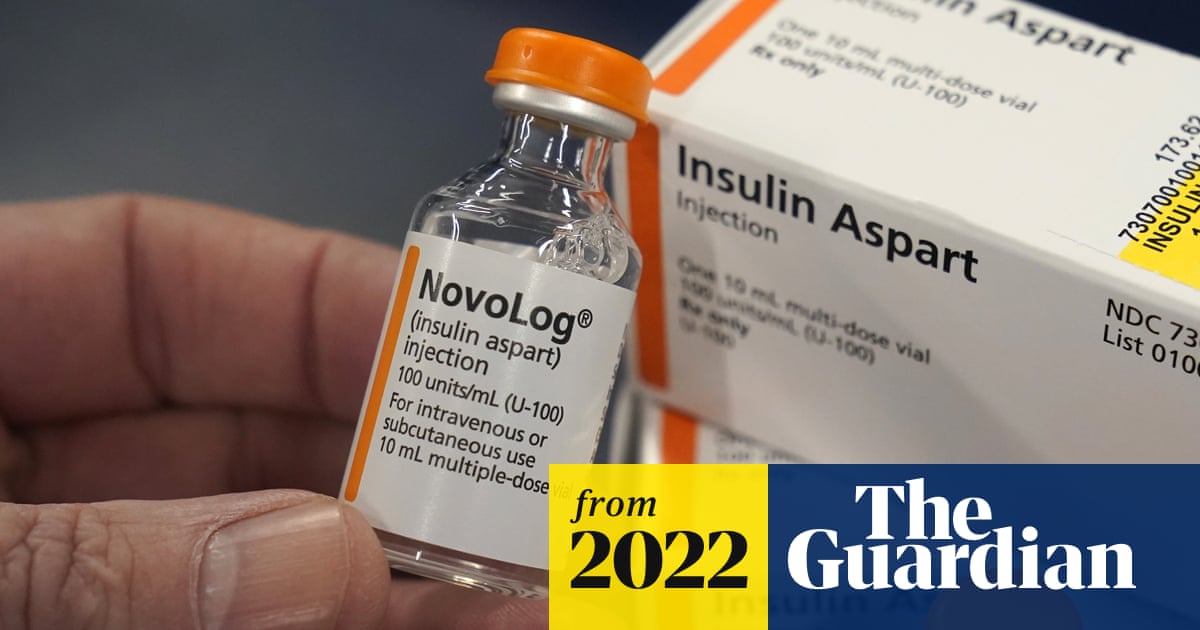

"So, if you can't afford to pay for your medicine, you just die?"

That was the question posed by a fellow Redditor in a forum discussing the U.S. health system. The person who posted was from a European country with socialized medicine and they were mystified at the idea of a modern, developed nation, where people could be denied medical care because they couldn't afford it.

My first inclination, as an American, was to dissemble: "Of course, people don't just die!" I thought.

They can apply to the pharmaceutical manufacturer for a discount. Many companies offer them. They can take out a personal loan. Many people do. Medical debt is a leading cause of personal bankruptcy. People often ration their supply of expensive medications, taking less than the recommended amount, to not run out.

But, ultimately, I had to agree with another Redditor, also from the U.S., who responded that, yes, if a person were unable to take on debt to pay the cost, ultimately they would die for lack of ability to pay.

To be more precise: First, they would probably qualify for a temporary discount through one piecemeal program or another, then they would spend their life savings, burn through their family's life savings, borrow and beg for money, then, when they couldn't borrow more money or pay the previous debt back, and the Go Fund Me didn't come through, they would cut back on the medication, probably suffer a series of medical complications requiring even more expensive medical care they couldn't afford, then they would die.

The 'best healthcare in the world'

Americans are often told that they have access to the best healthcare in the world. We are raised hearing this.

The United States does lead the world in funding the medical research that leads to new treatments, technologies and medicines.

Yes, even with the Trump administration's Department of Government Efficiency eliminating hundreds of clincical research grants, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) is still the largest public funder of biomedical and behavioral health research in the world.

If you are rich enough to pay for it, you can access almost any lifesaving treatment that exists. People from other countries often travel to the U.S. to get the care they need.

The problem is, more and more Americans aren't wealthy enough to pay for it. The cost of care has risen astronomically in recent years.

Where lack of access to healthcare used to mean that uninsured people had a hard time affording treatment. Now, even people who have health insurance are finding that they can't afford the premiums or co-pays. In some cases, even the cost of covered services and medications is too high.

As a whole, Americans pay more for healthcare than people in any other large, developed country in the world. But, their basic utilization rates are lower - meaning they go to the doctor or hospital less often than their counterparts in other countries.

And, health outcomes for a variety of conditions are worse than in peer nations.

According to the most updated internationally comparable data available, the U.S. has higher prices—particularly among private health plans—for many healthcare services. Meanwhile, utilization of many services, including doctor’s visits, number and length of hospital stays, and a variety of inpatient surgeries, is lower than in many comparable countries. As a result, the evidence continues to support the finding that higher prices – as opposed to higher utilization – explain the United States’ high health spending relative to other high-income countries.

- Peterson KFF Health System Tracker. Health Spending: How do healthcare prices and utilization in the United States compare to peer nations?

If you've never known any other system, it can be easy to believe that the health care people get in other countries isn't as good - even if it is more affordable or accessible.

Conservative politicians used to deride universal care with the more loaded term "socialized medicine" because, obviously, anything socialist must be bad, right?

The standard argument is: There is simply no way to ensure Americans access to healthcare without a) major sacrifices in quality or number of services available, or b) the government going broke giving everyone free healthcare on demand.

Having now lived in two different countries with socialized medicine - a.k.a. universal healthcare - I can tell you this is not true.

What universal care is really like

From 2006 to 2009, I lived in the Republic of Korea and was covered by its National Health Insurance Service. My daughter was born there, and I received state-of-the art preventive health care, maternity care, and a hospital delivery that I think we paid around $200US out-of-pocket for. I always got to choose my own doctors. And my daughter also got great baby and pediatric care and all of her standard vaccinations.

All residents in Korea with a sufficient level of income are required to participate in the national health plan, with premiums calculated on a sliding scale based on income. Government subsidies cover the cost for people with lower incomes.

The Korean health system has faced serious challenges in recent years due to an imbalance between health care services available in rural areas versus urban areas. There are also shortages in the number of providers in some clinical specialties (notably, pediatrics). But health care in Korea still ranks near the top in many global measures of quality, including access, efficiency and treatment outcomes.

I now live in Germany, which also has universal care, but with a multi-payer system instead of single payer. In Germany, all residents are required to maintain health insurance, either through the government-regulated statuatory health insurance (SHI) plan or by purchasing private insurance. Only people with incomes above a certain limit are eligible to opt out of SHI and purchase a private plan. And, patients with no or very low incomes are covered by government subsidies.

Our family participates in an SHI plan, as does almost 90 percent of the population.

I wrote more about the German health system here:

As it was in Seoul, my experience here has been good. No system is perfect. But I have always been able to get appointments with specialists that I have needed to see, have always been able to choose my own doctor, and never had a problem paying for my services or medications.

There are no surprise medical bills. If the doctor thinks I could benefit from having a particular screening test that is not covered by SHI, for example, they are required to tell me, up front. And, they have to tell me how much I would need to pay out of pocket if I still want to have it done. All medically necessary diagnostic tests and treatments are covered.

Why it hasn't worked for the U.S.

If I had to summarize the common elements I have observed in societies with universal healthcare, it comes down to two key things:

- First, a core belief in the value of a strong social safety net - with healthcare seen as a natural part of it;

- Second, the collection of as many people as possible into one shared risk pool - premiums paid by healthy members help pay for the costs of members with chronic illnesses or injuries + people with higher incomes pay more and subsidize people with lower incomes, with everyone receiving the same access to care.

But such emphasis on community interdependence and connectedness is anathema to much of American society. And this is the key, in my opinion, to why our system of healthcare developed differently, and why it has been so difficult to reform.

Sawbones is a podcast about medical history. This episode, from 2017, talks about the way that the U.S. health insurance system - with most Americans having coverage linked to their employer - evolved and why that is different from health plans in other countries.

Many Americans idealize individual self-reliance and independence. We are taught, from a young age, that it is a moral imperative to "pay your own way" without asking for help or handouts.

Beneficiaries of the what limited social safety net programs do exist are often stereotyped as people who are lazy and/or cheating the system, even though the data don't support this. Most non-disabled adult recipients of federal food assistance and Medicaid, for example, are employed.

So, the concept of a wealthier person paying more into a system for the benefit of someone who is poor - or a healthy person required to pay into a fund for services they may not need - is anathema to many.

That's not to say these Americans are stingy or selfish. Many of them willingly give money to charities or contribute money to help people they know in need. But they don't want to have to do it.

And many people seem to believe that they, themselves, will never have the misfortune of getting an illness or injury that will outstrip their insurance coverage or their ability to pay.

Like what you're reading? Sign up to receive regular updates by email and to access to the comment section. Memberships are free and help support my work.

The 'rationing' we were warned about

I am old enough to remember when health care reform – the idea that we should change the profit-driven funding model that we currently have – first became a serious public policy issue in the United States.

This was in the 1990s, just after the election of U.S. President Bill Clinton. First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton chaired a task force to develop a plan to provide universal health care to Americans.

The Clinton Health Plan would require American citizens and legal permanent residents to enroll in a qualified health plan, either independently or through their employer, with government subsidies available for people to poor to afford the premiums on their own. (This is almost exactly the kind of health system that exists in Germany.)

A national health board would be established to decide on a base level of treatments and conditions to be covered by the health plans, as well as caps to the amounts that physicians and hospitals could be paid for their services.

The plan was vociferously opposed by conservative politicians, as well as the American Medical Association and the Health Insurance Association of America, which both launched massive advertising campaigns designed to defeat the legislation.

Remember 'Harry and Louise?'

I do.

Politicians, lobbyists and physicians groups warned that the government would "ration our health care" – deciding who would have access to lifesaving medicines and treatments.

They raised the spectre of parsimonious government bureaucrats in a back room denying grandma's chemotherapy or dad's coronary bypass to give free health exams to poor young people.

Isn't so much better to have indivdual freedom to choose what care you receive?

Of course, they failed to mention that private, for-profit insurance companies themselves ration access to treatments and services, limiting the care they will pay for in order to minimize payouts and maximize profits to their shareholders.

Legislation to enact the Clinton health plan never even made it to a vote in Congress and it would not be until the Obama administration that health reform would be attempted at the federal level.

Next up: In part 2, we'll cover 'managed care,' why the ACA didn't fix everything and the current state of healthcare in the U.S.

Let me know what you think! Do you have an experience with health care in the United States that you want to share? Did I get something wrong? Log in to the website and tell me about it.

Member discussion