American Exodus

A new wave of immigrant narratives tell the human stories behind the numbers.

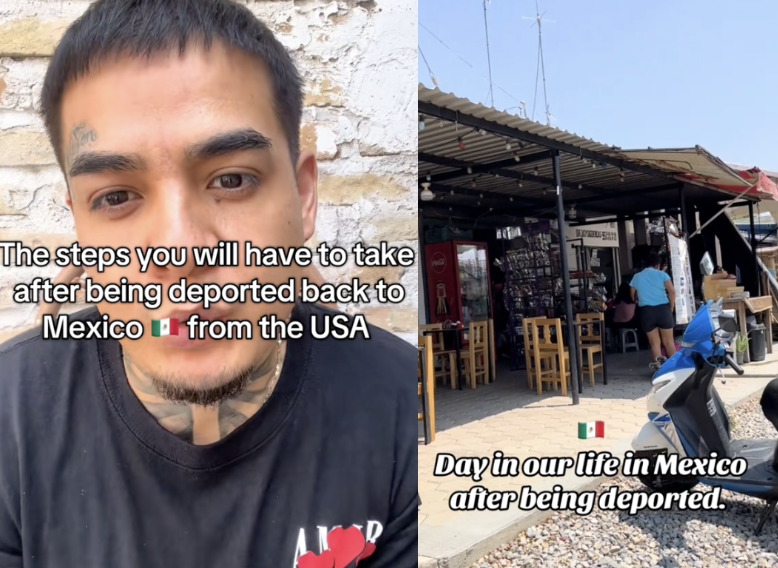

Román Quintanilla is a rising star on Tiktok, with just over 50,000 followers in just under two months on the platform. In a recent post about a trip to Cozumel, he shared a discount code for a tour boat excursion.

But Quintanilla is not an influencer. And he is the first to tell people he's not monetized on that or any platform.

His "lifestyle content" documents his new life in Mexico following deportation from the United States. Things like learning to get up early to fill the cisterns for his 'rancho' in Coahuila with water for the single hour the water is on during the day. Or, paying a friend to take him to fill up his propane tank so that he can cook and take hot showers for the week.

Raised in the U.S. after being brought there by his parents as a baby, he doesn't speak a lot about the circumstances that led to his expulsion from the only home he's ever known; he prefers to focus on the future.

"I just refuse to sit and cry about it," he wrote in the comments to a recent video. "I'm trying to make the best of it."

His is just one of many "life after deportation" channels that have emerged in the wake of the Trump administration's ramped-up efforts to deport undocumented immigrants.

In the midst of what has been pledged to be the largest mass deportation in American history, these stories show the human dimension behind the bombastic headlines.

Francisco Hernandez-Corona, former DACA recipient and graduate of Harvard University, self-deported to Mexico with his husband, earlier this year.

"Because immigrants in the U.S. aren’t safe," he writes in response to those wondering why he left after obtaining legal status. "Because every time we turn on the news, we see people like us, brown, undocumented, hardworking, being torn from their families. At Home Depots. At construction sites. At immigration hearings. Children in handcuffs. Mothers screaming for their kids. Because even after decades in the only country we’ve known, our humanity is still questioned.

So we left before we were taken. We chose dignity and freedom over fear. We chose to live."

Other channels have been started by citizens who have voluntarily left the U.S. to live with deported spouses or children to live with deported parents.

"These videos speak to deportees’ experience of the US legal system," writes Rosie Snow at 404 Media, where I first read about this trend. "Their detentions, and the fear and administrative burden of being undocumented. They provide community, resources, and advice for those going through similar things."

Expats to emigres

Ironically, this is occurring at the same time an increasing number of U.S. citizens are choosing to leave the country.

In 2024, I wrote about the American "quiet diaspora" of citizens living abroad with only very vague ideas of returning.

And Laura Skov, an American living in Sweden who pens the Substack newsletter, Notes from Exile, has observed a similar shift.

"Americans abroad don’t look like expats anymore and I know why: They’re not going home," she writes. "Whatever I am, I’m not going back there, and neither are a lot of those chipper corporate expats. They’re trying to finagle a way to stay here, because the current state of American exceptionalism? It’s sitting in a for-profit prison in El Salvador with its head shaved."

Increasingly, Americans abroad are experiencing life on the immigrant side of the coin, with much of the same social and political stresses that stigmatize those back home.

I wrote about that on my Substack, Alte Frau-New Life, about life in Germany--where the economy depends on the labor of millions of immigrants, but struggles to integrate or accept them.

Americans are used to thinking of their country as a place that people want to move to, not away from. So we are used people in other countries seeing us in a similar way – as privileged and special guests – not desperate newcomers, grasping gentrifiers, or stealers of jobs and corrupters of cultures.

Increasingly, we are some or all of those things. Or just vulnerable people trying to survive the best way they can.

Janelle Hanchett, late of California and the blog Renegade Mothering, now a memoirist and writing coach living in Haarlem, writes:

"I could tell you how I fell into the deepest depression of my life, how angry our adult child was that we moved here, how we sent our older son to the wrong school and paid for it dearly, literally and figuratively. I could tell you how covid hit six months after we arrived, and my world got even smaller than it already was, until I gave up trying to make a life here, trying to find friends, community, and my life became two bike rides a day to take the kids to school and pick them up, a trip to the store if I absolutely could not avoid it, a pack a day of cigarettes smoked alone on my porch while I stared at my phone. I could tell you of our dreamy trips to Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, Greece, the Alps.

I could tell you a thousand stories of how much I hate it here, how much I love it here, how much I do not, in the end, regret leaving."

According to the United Nations, more people than ever before are migrating internationally.

Today, more people than ever live in a country other than the one in which they were born. According to the Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), in 2024 the global number of international migrants was 304 million, a figure that has nearly doubled since 1990 , when there were an estimated 154 million international migrants worldwide.

The demographic impact this will have--as huge numbers of people shift across the globe and world powers shift--will likely only be understood in hindsight.

In the meantime, these narratives serve as a window into the lives of the people on the move--debunking the myths and conspiracies and– for better or worse – reshaping our world.